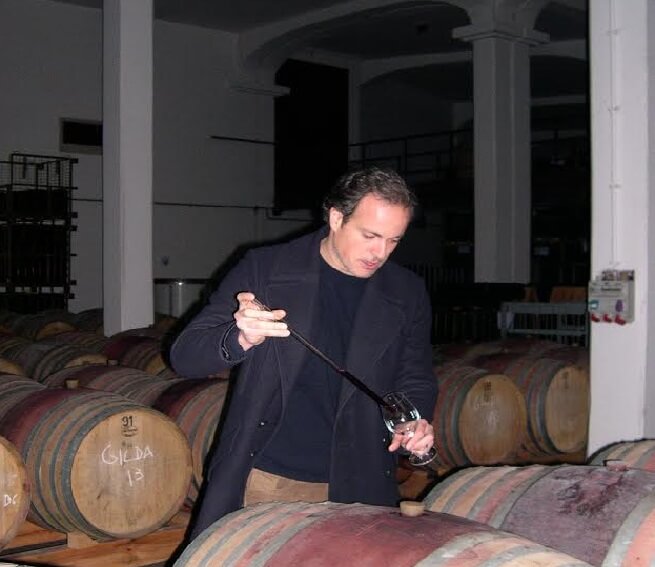

Renowned Master Sommelier João Pires shares some secrets, but not the big one!

Text Sarah Ahmed

Filmed in six countries over two years, the American documentary “Somm” follows four would-be Master Sommeliers as they endeavour to pass the “massively intimidating” Master Sommelier Exam and join the Court of Master Sommeliers – “one of the world’s most prestigious, secretive, and exclusive organizations”. A member of the Court of Master Sommeliers since 2009, Lisbon-born João Pires has enjoyed an illustrious international career, latterly in London at two star Michelin restaurant London’s “Dinner by Heston“. Currently taking time out with his baby daughter, I caught up with Pires who reflected on what it takes to get to the top.

João Pires – Photo provided by João Pires | All Rights Reserved

1. A sommelier has been described as the bridge between the chef and the winemaker. Do you agree?

Not really! A sommelier is the bridge between the winemaker and the guest.

2. In your opinion what qualities make a great sommelier?

A great sommelier is one who understands that, above everything, it is the guest that counts and not his own pride.

3. And what makes a great wine list?

A great wine list is the one which sells. If it sells it is because it is guest- orientated and therefore the guests buy. It is definitely not the list designed for awards although some good awarded wine lists are very good. But not the other way around!

4. Ordering wine can be intimidating, especially when the wine list is huge. How can diners get the best out of a sommelier?

Speak with the sommelier, challenge him. I have seen small, straightforward wine lists where one can hardly buy anything and I’ve seen 1000 bin and bigger wine lists which guests can easily go through if well guided by a good sommelier. It is not the size but the engineering of the wine list that counts (and the sommelier of course).

5. What is your approach to food and wine matching?

Understand the weight of the food, be guided by the main colour of the dish, acidity balance is the key. Understand the occasion and respect guests’ budget.

6. Have you ever encountered a dish which has defeated you in terms of coming up with a satisfactory wine match?

Oh yeah many times and sometimes it is almost impossible to find the wine which we think is the right match. Well in a table of four people there are at least four possible wine matching right? And which wine to go with a 6 cheese board from light goat to old and hard cheddar or salty blue cheese? And how to match a Chinese dinner for instance when they share so many different foods at the same time? The wine world needs to understand that food & wine matching is not always possible.

7. Is food and wine matching necessarily a compromise; do you welcome the trend towards more wines by the glass and tasting menus?

Yes I agree and by the glass is a good solution. But if a bottle has been ordered try to recommend anything ‘right in the middle’ like a Pinot Noir to go around the table if there is a fish and meat order for instance.

8. Carte blanche, what would you order (wine/food) for your last supper?

Champagne, more champagne and why not fresh oysters by the sea?

9. Celebrity chefs have transformed luxury hotel dining. What is more important, the culture of the chef or the culture of the hotel or are they symbiotic.

Both are important and they collide so many times, not an easy one to manage. Chefs are good ‘restaurateurs’ and hotels boast good ‘management skills’.

10. Luxury hotels have an international client-base and you yourself are widely travelled having trained in Paris, worked the floor in Portugal, Toronto and London and trained sommeliers in Macau, Morocco and the Philipines. What cultural (international) differences in wine consumption have stood out to you?

Working in a high profile three Michelin star restaurant in Paris is something you can never forget. The pressure and attention to detail is such that it is almost insane. In terms of wine consumption French wines dominate with the exception of those countries where wine is part of the culture, such as Italy, Spain or Portugal where people, understandably, drink local wines.

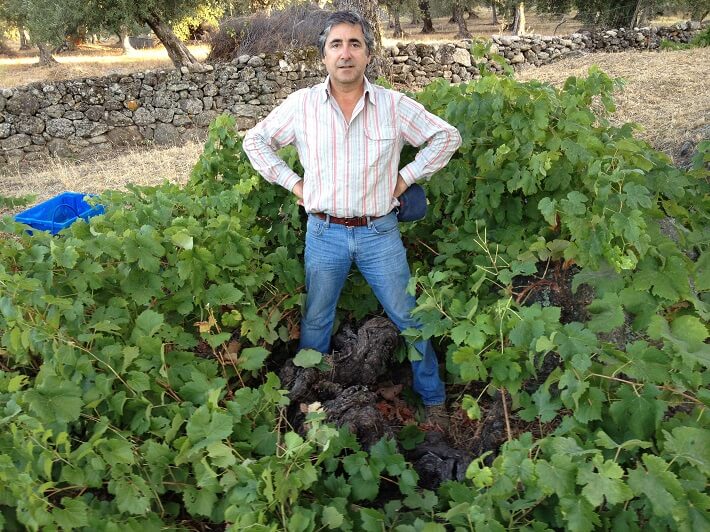

João Pires – Photo provided by João Pires | All Rights Reserved

11. The American critic Robert Parker recently railed against a perceived fashion for obscure grapes on wine lists. How important is it to introduce diners to new wine experiences and how easy is it to persuade high rollers not to order the predictably prestigious?

Who is Robert Parker? And what is the meaning of ‘obscure’? Anyway, more and more ABC (anything but Chardonnay or Cabernet) is over. Why not persuade high rollers with top prestige wines? We run a business and on my side there is nothing wrong to order and drink a DRC (Domaine de la Romanée-Conti), Château Pétrus or Champagne Salon. A shame I cannot do it myself on a regularly basis. Although on the other side less known grape varieties and different tastes at good prices is a paramount consideration because people are more open- minded than ever and keen on different tastes.

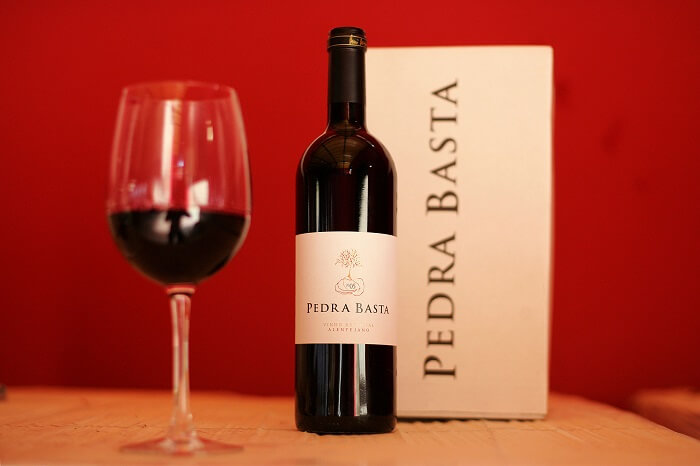

12. Port and Madeira are de rigueur on a classical wine list yet, outside Portugal, Portuguese table wines have struggled to make their mark. This is starting to change. What do Portuguese producers need to do to challenge this state of affairs?

Well first of all Port and Madeira are not (unfortunately) de rigueur on a classical wine list and in this country they do not sell. But unfortified Portuguese wines are step by step coming up. It will take time for them to feature on top wine lists but things are getting better. Portuguese producers need to get together (some are already doing that and with huge success).

13. Which Portuguese regions, grapes, wine styles and producers stand out for you?

I must say there are good wines all over the country and better than ever. You can buy really good quality wines between 3 and 10 euros in Portugal which is quite difficult in UK supermarkets. Personally I love the Douro, Dão and Bairrada for reds and Alvarinho for white. But, having said that, one can find great wines in the Alentejo, Lisboa and other regions.

14. You have an enviable curriculum vitae. Which of your professional accomplishments makes you most proud?

Becoming a Master Sommelier.

15. With even fewer Master Sommeliers than there are Masters of Wine (219 versus 313), it is notoriously hard to become a member of the Court of Master Sommeliers. Why would you recommend it to others?

I’m not sure I’d recommend it. It is so demanding and you sacrifice so many things in your personal life that it is hard to say go for it. But despite this you learn a lot and it is very rewarding indeed.

16. What impact does it have on a sommelier working in a one, two and three Michelin star restaurant?

A huge impact. There is nothing more serious than wine for revenue and high service standards. And the higher the rank the more demanding and difficult it is. Very stressful but extremely rewarding (and I am not talking about wages)!

17. Which experience taught you the most and/or who has most influenced your career?

The European Sommelier Contest in 1994 which was sponsored at that time by Ruinart Champagne. I was representing Portugal and that was the moment I decided to dedicate my life to wine seriously. And my first stage in Paris in 1996 at the 2 Michelin-starred restaurant ‘Les Amassadeurs’, Hotel Crillon. I was blown away with the sommeliers and the chef sommelier Frederic Lebel.

18. How does it feel to have left the floor? What do you miss most? And what do you least miss?

I am feeling great after 25 years doing that. I must say I don’t really miss it a lot. What I do miss is the daily exercise and, most of all, my guests.

19. What next?

Good question but I cannot tell you right now. I am enjoying my little 4 month old baby girl Isabella. I have been feeling extremely happy and blessed.