Aphros: At the cutting edge of Biodynamics in Portugal

Text Sarah Ahmed

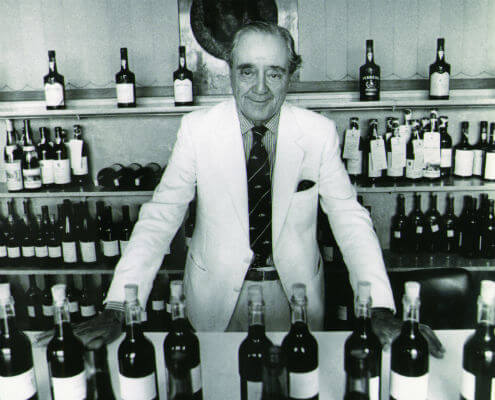

Vasco Croft puts the dynamic into biodynamic, the holistic method of farming of which he has been a pioneer in Vinho Verde (and which you can read all about on his website) here.

Since I last visited the former furniture designer and trained architect’s Vinho Verde estate in Ponte de Lima in 2010, the portfolio has undergone a facelift with a new name (Aphros not Afros) and labels.

Croft explains the name change was prompted by a request from the USA, his biggest export market, who were concerned about possible confusion with Africa or the African hairstyle. Fortunately (Croft doesn’t strike me as the type to compromise) he says, “because this is the Greek way of spelling, it is in tune with the origin of the name, meaning the Mythical Foam from which Aphrodite arises.” So all’s well that ends well.

As for the labels which have a motif of three interlocking circles, these were developed from engravings by his cousin José Pedro Croft, an international plastics artist. It wasn’t just the family connection which appealed to Croft. He explains, “I hope this image will be a refreshing wind in the world of wine labels and bring contemporary art and wine close to each other.” Speaking of which, I reckon Portuguese wine labels are improving. They’re more colourful and characterful, which helps wines to stand out on the shelf and gives customers an inkling of the people behind the wines. A very good thing.

But it’s what’s in the bottle that really counts and, at Aphros, the changes go well beyond skin deep. Croft has been steadily expanding the portfolio with an ambitious oaked Vinhão (Aphros Silenus), Aphros Rosé, Aphros “Ten” (a low alcohol, 10% abv, Loureiro), Daphne (a very exciting Loureiro which undergoes skin contact) and, most recently, AETHER (a 50:50 blend of Loureiro and, to my surprise, Sauvignon Blanc, a non-native).

Photo by Sarah Ahmed – All Rights Reserved

The growth spurt at Aphros extends to vineyards as well as wines. Croft acquired and planted Quinta de Casa Nova in the neighbouring parish of Refoios in 2009, which has been cultivated biodynamically from the beginning. He plans to convert the dilapidated house into a wine bar and, this year, has started work on a new winery with the capacity to produce 120,000 bottles. And after that, he might just play around with an Aphros Pinot Noir from Quinta de Valflores, the vineyard that he has rented next door on a long-term lease from the Bossert family from Oregon, USA (which explains the Pinot Noir)!

Meanwhile the pocket-sized original winery at Croft’s family’s original estate, Quinta do Casal do Paço (which, in accordance with tradition, is located under the house), will continue to be used for the smaller batch, hand-crafted wines. Owned by his family since the seventeenth century, until Croft started the Afros/Aphros brand in 2005, grapes were sold to the local co-operative. Croft re-structured the vineyards and started cultivating them biodynamically with input from French biodynamic consultants, first Daniel Noel, now Jacques Fourès; the estate has been fully Demeter (biodynamic) certified since 2011. It is here that compost (pictured) is seeded with biodynamic preparations made exclusively from organic matter, which are applied in the vineyard according to planetary rhythms. Homeopathic quantities of the preparations are first diluted with dynamised water from the flow form (pictured) and further energised by stirring in the copper vat (pictured). Experimental bio-stimulants (pictured) are also prepared here.

But it’s not all about wine for Croft. He emphasises “[J]ust making good wine is not enough”. As he sees it, “the question of going organic or biodynamic is really an issue of consciousness primarily, concerning understanding and caring for Nature and developing a deeper relationship with the Earth of which we are a part.” He asserts “it is not just a technique, much less a ‘marketing’ option.” It’s why his vision extends “to creating an agricultural/cultural centre” with a permaculture hill and “food forest” at Quinta do Casal do Paço – a “sanctuary” for different plant species. Increasing the estate’s biodiversity in this way helps nature to self-regulate (for example, it encourages those natural predators which kill vineyard pests or discourages pests by providing them with something to eat other than vines!). And the food forest will provide produce for the farm-to-table wine bar which is planned for Quinta de Casa Nova.

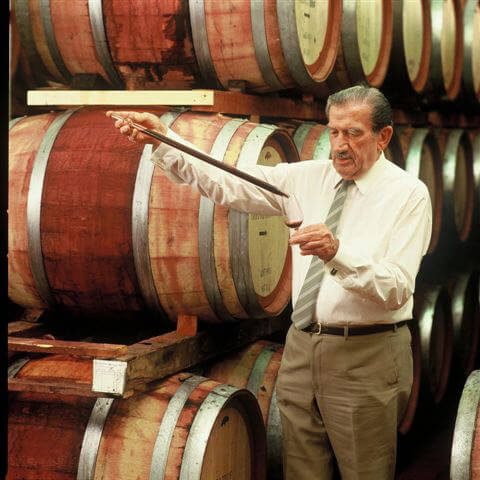

I’m looking forward to visiting the wine bar on a future visit but, meantime, I can wholeheartedly recommend seeking out the Aphros range. Last month I tasted the latest releases (reviewed below) with Croft’s consultant winemaker Rui Cunha and took the opportunity to ask Cunha about the benefits of working organically and biodynamically. Laughing when he recalls “people thought it was a bit crazy early on,” Cunha had met with German and French biodynamic practitioners during his travels but his hands on baptism by fire came at Quinta de Covela. He says “it was frightening” when Nuno Araujo (the Vinho Verde estate’s former owner) announced today we start converting the entire estate to biodynamic cultivation. This was around 2004 at a time when Portugal’s winemaking courses didn’t mention organic let alone biodynamic farming.

Photo by Sarah Ahmed – All Rights Reserved

Like Croft, Araujo employed the French consultant Daniel Noel and, Cunha says, “we saw an immediate increase in the quality of the grapes. They were less productive and suddenly more balanced; with time, they became more consistent in yield.” He adds maturation has been slower and acidity higher, which has proved particularly useful in a hot climate. Of course the ultimate test is taste as to which Cunha says “grapes taste much better.” He observes it’s no different to comparing fruit from your own tree with shop bought fruit which has been cultivated conventionally (i.e. with chemical inputs – fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides). As for the specifics Cunha freely admits that he cannot explain why some biodynamic practices work but he has seen first hand how biodynamic preparation 500 (composted cow manure) results in much more soil vitality and just 200 grams of 501 (quartz powder) can have a significant impact on growth – “leaves become thicker, which makes them more resistant to the sun (sunburn) and insects.”

Croft has noticed that more Portuguese producers are working organically or biodynamically these days, even if they do not certify their wines. According to the Instituto da Vinha e do Vinho, Portugal now has around 2,500ha of certified organic vineyards which is cultivated by 485 grape growers and 52 certified organic wine producers. Referring to “a world trend in respecting land and tradition and authenticity in wines” in his opinion “[I]t is all good, because the agro-chemical age is ethically and scientifically gone, it belongs to the past even it will still linger for a while out of inertia.”

Aphros Aether 2013 – Photo by Sarah Ahmed – All Rights Reserved

Aphros Ten 2013 (Vinho Verde)

Ten was first made in 2011 and is sourced from Loureiro grapes from younger vines. Its name is a reference to low alcohol content (you guessed it, around 10% abv). The 2013, a tank sample, is very pretty – this off-dry Loureiro is classically floral with talcum powder hints to its pure, crystalline flavours of lime and grapefruit, a hint of citrus peel too. Lively, mouthwatering acidity maintains focus and balance (better than in the 2011 vintage, which lacked a bit of verve). Very good; a great quaffer. 10%

Aphros Loureiro 2013 (Vinho Verde)

A number of factors make for a more serious, concentrated, structured wine. First, the fruit comes from older vines. Second, the grapes see around 4-6 hours skin contact (in the press) and, once pressed, the juice is fermented at slightly higher temperatures. It is aged on the lies with batonnage, which brings body and complexity. So while it has Loureiro’s tell tale floral lift, it is much more firmly structured, focused and mineral. Very fine, long and persistent. I reckon purer than previous vintages. Cunha agrees pointing out that this vintage benefited from the acquisition of a press (previously the press was rented and was not always available at the optimum time in terms of grape harvest). Now the grapes can be picked at precisely the right moment and go straight to the press. No hanging around which explains this vintage’s lovely precision. Very good indeed and has ageing potential. 11.5%

Aphros AETHER 2013 (Minho)

This is a 50:50 blend of Loureiro and Sauvignon Blanc, all estate grown. Cunha explains he loves Sauvignon, but there is a business rationale to this wine too. Aphros are using the better known French grape as “a door opener” for export markets. For me AETHER is a wine of two halves. The Loureiro leads on the nose with its pretty, ethereal even, floral, talcy notes. The Sauvignon dominates the palate, which has a chalky minerality, leafy blackcurrant bud notes and a crisp, more punctuated finish than Aphros’ Loureiros. It’s crisp and clean with punchy Sauvignon varietal character but, I have to admit, I’d personally gun for the more charming Loureiro every time! 12%

Contacts

Quinta Casal do Paço

Padreiro (S. Salvador)

Arcos de Valdevez 4970-500 Portugal

Tel: (+351) 91 42 06 772

E-mail: info@afros-wine.com

Website: www.aphros-wine.com