Text Sarah Ahmed

Parallel lines: Casa Ferreirinha Barca Velha & Penfolds Grange – The forging of two icons

My passion for the wines of Portugal and Australia (the focus of my writing), often raises eyebrows.They are so very different people say. Which, of course, is part of the appeal! Yet there is also a very striking parallel to be drawn between the evolution of those wines which mark a watershed in each country’s history of table winemaking – Portugal’s Casa Ferreirinha Barca Velha and Australia’s Penfolds Grange.

Both full-bodied red wines were officially launched with the 1952 vintage. Produced by plucky, gifted winemakers (Fernando Nicolau de Almeida and Max Schubert) who were both grounded in fortified wine production, neither had the technology or tools which table wine producers take for granted today. Both men drew their inspiration from Bordeaux, the fine wine capital of France (arguably the world), which they independently visited in the mid-twentieth century. Small wonder Barca Velha and Grange have been dubbed Portugal’s and Australia’s “original first growths.”

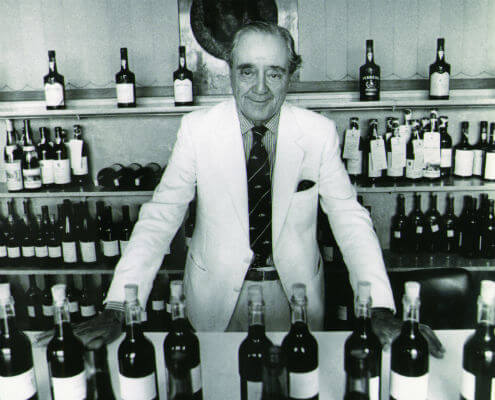

Barca Velha 1952 – Photo provided by Casa Ferreirinha | All Rights Reserved

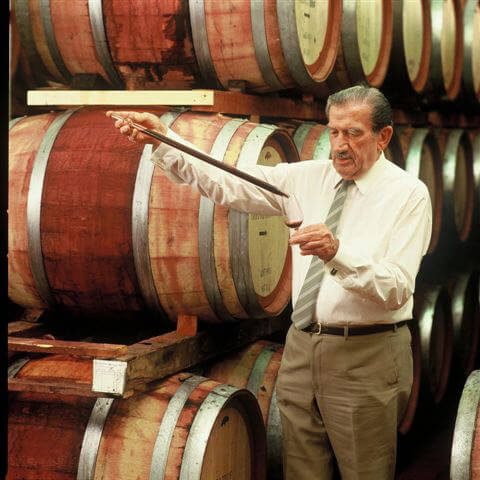

Ironically, neither Schubert’s nor Nicolau de Almeida’s initial contact with the Bordelais centred around making a super premium red wine. Nicolau de Almeida met the University of Oenology in Bordeaux’s famous professor Émile Peynaud when Peynaud visited Casa Ferreirinha in the late 1940s. Peynaud was commissioned to help find a solution to the high malic acid levels of red Vinho Verde. Nicolau de Almeida seized the opportunity to show Peynaud his experimental Douro red wines. Says Nicolau de Almeida’s son João Nicolau de Almeida (Chief Winemaker at Ramos Pinto), “when Émile Peynaud tasted them he was surprised with the quality and advised my father to put Vinhos Verdes aside and dedicate his time to Douro wines.”

Shortly afterwards Nicolau de Almeida visited the main wine-producing regions of France (Burgundy, Bordeaux), also Rioja, Spain in order to study those red wine fermentation techniques which would help him to maintain aroma and freshness (properties that tended to be lost with the heat of the Douro). But there was a problem. In contrast to Bordeaux, Burgundy and Rioja, the Douro had no temperature controlled fermentation tanks because very few estates had electricity (Douro wines were fermented in shallow, open lagares where it was impossible to control the fermentation temperature). Not one to be easily put off Nicolau de Almeida’s ingenious solution was to build a double walled wooden fermentation vat whose outer wall could be filled with ice – no mean feat since the ice had to be trucked in from Oporto, 12 hours away!

Fernando Moreira Paes Nicolau de Almeida

Taking a more conventional leaf out of the Bordelais’ book, he also decided to pump over the must rather than foot tread the wine, which was totally new in the Douro. Another innovation involved ageing the wine in oak barrels which were kept in a new (cool) underground cellar which was specially constructed at Quinta do Vale Meão.

Here a team was installed to monitor the barrels for malolactic fermentation, after which the barrels would be topped up in order to maintain the freshness which Nicolau de Almeida had striven so hard to achieve. Indeed, while Meão was the original source of Nicolau de Almeida’s powerful experimental wines, by 1952 he had decided to produce a blend of Meão grapes with grapes from another cooler Douro Superior vineyard in Mêda. Located at 600 metres altitude, the Mêda fruit enhanced the freshness and so balance of the final wine.

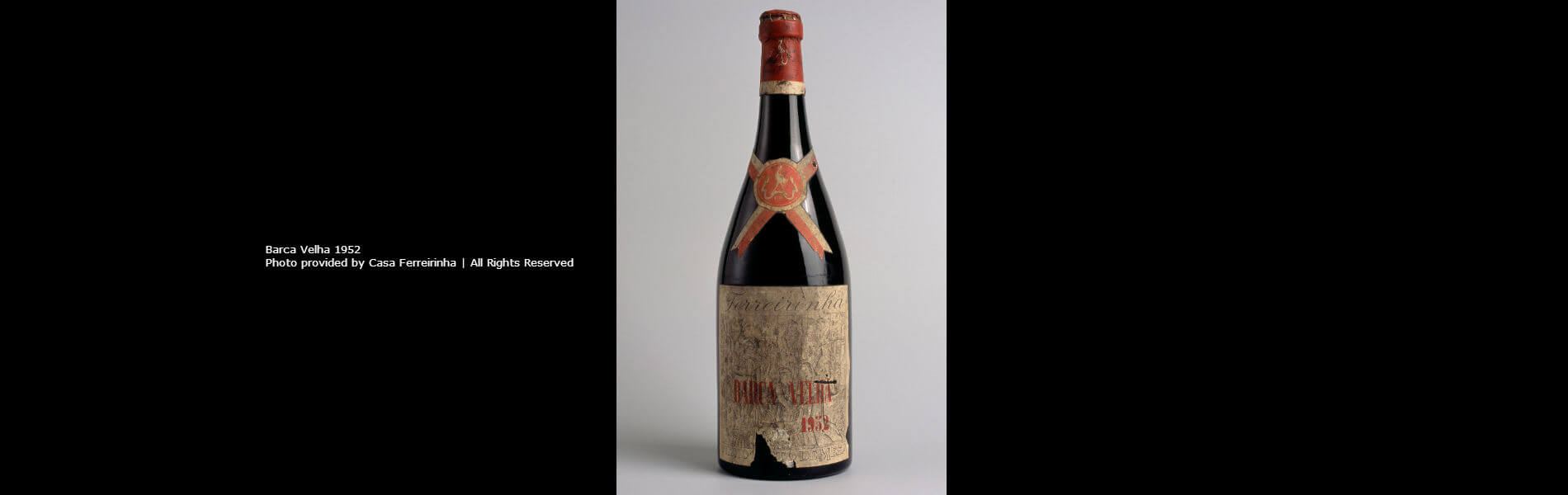

As for Schubert, Penfolds (which, like Casa Ferreirinha, was then principally focused on fortified production at this time) despatched the young Chief Winemaker to Europe in 1950 to investigate advances in sherry and port production. But when he fetched up in Bordeaux, Schubert was taken under the wing of Christian Cruse of négociant firm Cruse et Fils Frères. Cruse introduced him to Bordeaux’s first growths (including wines between 40 and 50 years old, which impressed Schubert for being “still sound and possessed magnificent bouquet and flavour”).

While visiting leading Bordeaux estates, he gained an insight into the practices which lay behind these long lived but refined wines, in particular racking wines into new oak barrels to complete their fermentation and tannin fining. On his return to Australia, Schubert immediately employed both techniques, also rack and return, when he made the first prototype Grange in 1951. His daughter Sandie Coff recalls “dad told me he designed Grange in his head in the plane on his way back from Europe. It would be a truly Australian wine [it is principally made from Shiraz, sometimes with a dash of Cabernet Sauvignon] but able to rival the wonderful French wines [which were principally Cabernet Sauvignon Merlot blends] he had seen.”

Max Schubert of Penfolds – Photo by Sarah Ahmed | All Rights Reserved

However, while the first release of Barca Velha (a blend of classic Douro grapes) appears to have met with immediate acclaim, the first vintage of Penfolds Grange fell well short of convincing either critics or consumers that it rivalled top France’s best wines. In a paper which he delivered at the first Australian National Wine Symposium in 1979 (which is published in “Penfolds’ book, The Rewards of Patience” by Andrew Caillard MW), Schubert recalled how the initial controversy about Grange “pained me no end.”

Early reviews included comments such as “a concoction of wild fruits and sundry berries with crushed ants predominating” and “[a] very good dry port, which no one in their right mind will buy – let alone drink.” Doubtful about its future, in 1957 Penfolds’ board of directors decided to cease production of Grange. Fortunately, Schubert continued in secret until 1960 when a tasting of bottle-aged examples of the 1951 and 1955 vintages at last won the company’s and critics’ respect. Suffice to say for many years now this powerhouse has been aged for five years prior to release.

For João Nicolau de Almeida, his father’s obstinate refusal in the face of “strong demands from the Board and from the market” to release Barca Velha until he believed it was ready to be served was critical to its early success. Following Nicolau de Almeida’s precedent, Barca Velha is only released after a minimum of several years’ bottle-ageing. Should you be lucky enough to experience a vertical tasting of Barca Velha or Grange, you will truly begin to appreciate the rewards of patience.

Leave a Reply