Text João Barbosa | Translation Bruno Ferreira

The wine lives in me, not just because I like the drink but for all that goes with it. There are more economy texts about this sector than (probably) historical, anthropological or sociological.

30 years ago there were taverns in Lisbon… I mean real taverns, not beautiful places with scenario and poor’s food for the rich. Many snacks that – now they call them tapas, in Spanish is cuter, just a provincialism – were served to draw drink, some were even offered.

Today is raffiné (forced foreignness, a provocation because of what I wrote above) to serve fried potato peelings and charge as if they were silver potatoes. Back then they were offered and salty. Another funny thing – this one is pathetic but it helps to explain why cod fish was affordable food to the poor – were the splinters. Yes, nothing more than the dry “faithful friend” with salt. It was cheap and salty, entertained the mouth and called for more glasses.

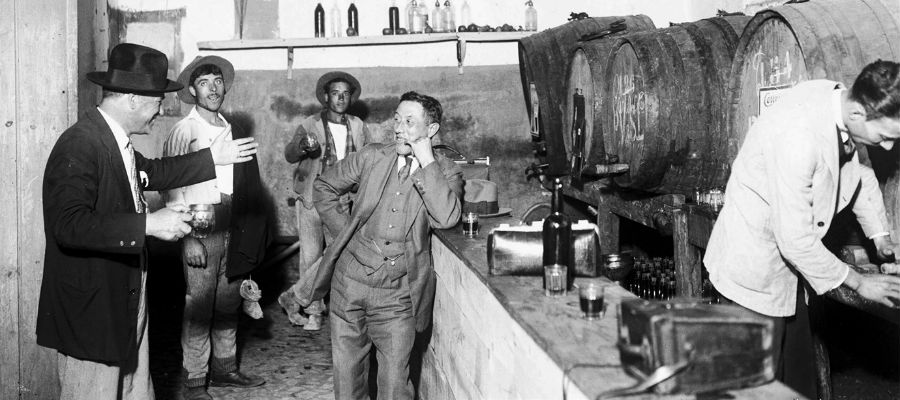

A tavern in Lisbon in Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa

Many taverns were also charcoal kiln. That meant the wine odors (bad), soot and sawdust got mixed together… yes, tavern’s alcoholics drank to the “limit”, the wood shavings were for easy cleaning… absorbers.

The taverns, nowadays exquisite, were ugly, nasty, smelly and poorly attended. The wine used to come in dirty wooden barrels of various sizes. For the nostalgic and romantic I say:

– No! Back then, the times were no better!

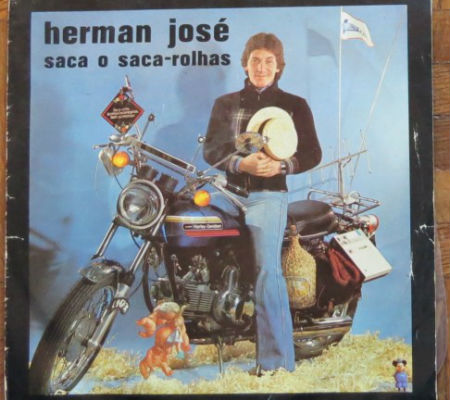

The text came to my mind because I was reliving the memories of a song from a brilliant Portuguese humorist. In 1977, the actor Herman José was also dedicated to music and released the disc (45 rpm) “Saca o saca-rolhas” (Draw the corkscrew). Besides the joke, the song is also a window to Portugal of 30 years ago.

Herman José’s record “Saca o saca-rolhas”

Bayberry Branch in wikimedia.org

«Saca o saca-rolhas, abre o garrafão, viver sem vinho não presta». (Draw the corkscrew, open the carboy, living without wine is no good”). This statement is (being generous) in the politically correct limit. Young people will hardly be aware of this and the foreigners certainly do not know it.

In the verses, in addition to consuming a carboy (five liters), it is also told of how the motorcyclists used to speed after drinking alcohol, risking a digestion stoppage by diving into the sea after the spree, and (as it appears) taking an extra passenger on the motorbike. Portuguese roads were a civil war, in the deaths’ department.

Of course there still exists some of that reality. However, it does not have the past’s indulgence and it is unanimously criticized. At that time, the wine was the main fuel that the Portuguese people used for getting drunk, more than beer… and spirit drinks were far from affordable.

This point deserves a historical framework. In 1974, Portugal stopped being a closed and controlled economy and was gradually opening up. In 1975, the colonies became independent, with financial implications. In the equation we have to put the oil crises, economic upheavals arising from political choices, etc.

If until 1974 the Scotch whiskey, for example, was “hidden” and the Spanish gin was tenebrous, the 1977 and 1983 bankruptcies, with interventions from the International Monetary Fund, made the border of alcoholic beverages visible.

The fresh money that flowed from Community sources, since 1986, helped change the paradigm. They have changed the various patterns of consumption, but the Portuguese still require for the wine to be cheap. They don’t even consider how much the producer invests, the risks and the prices at which he sells.

At the time of Herman’s corkscrew, consumption was very high and price very low – something also possible thanks to the production of vinho-a-martelo, a concoction that could also contain wine, but it was composed of a number of products that changed and altered it: falsification of foodstuffs.

The Portuguese are willing to pay one euro for a bottle of water or 60 cents for a coffee, but a wine above five euros is a piece of jewelry. I did the math and wine at the coffee’s price rate costs 15 euros (0.75 liters).

But I cannot finish this retrospective look without a popular verse, with the sarcasm of false naivety: ”À porta do Santo António está um ramo de loureiro, é uma pouca-vergonha fazer do santo tasqueiro” – “At St. Anthony church’s door there is a bayberry branch, it’s a shamelessness to make the holy, a tavern man”

At the door, the taverns had at the customer’s disposal, bayberry branches. Apparently, chewing these leaves makes the wine’s breath go away. Well, we can see that the revelers went back home tumbling down, but could prove their innocence when duely reprimanded by their wives because they didn’t have alcohol breath.

A convention: I know you know that I know you know that I know.

Leave a Reply