Blue Skies Drinking? The Rise of The Serious Rosé

Text Sarah Ahmed

If there’s a wine style which is firmly associated with summer and the holiday spirit it has to be rosé. Can it be any coincidence that Brazil, a country synonymous with sunshine and the holiday spirit, was the target audience for Mateus Rosé when it was first launched in 1942?

As for us Brits, when I interviewed Sir Cliff Richard a few years ago he told me that he has been a fan of, guess what, Mateus Rosé, since he bought his first house in the Algarve in the sixties. So it would seem that the “Summer Holiday” star’s holiday spirit has rolled on, in fact perhaps it’s the still boyish-looking singer’s elixir of youth!?!

Mateus Expressions – Photo by Sarah Ahmed | All Rights Reserved

But, over the last decade, there has been a major shift among consumers who, these days, are enjoying rosé year round and not just on holiday or in the summer. Indeed, last year in the UK, Rosé accounted for a record one in eight bottles of wine bought in supermarkets and off-licences, up from one in 40 in 2000. Now popular, even fashionable, the mainstay of sales has been sweeter, entry-level wines.

Though Mateus Rosé continues to outperform the market in this category, Californian brands such as Blossom Hill, Gallo and Echo Falls have been by far the biggest beneficiaries of the rosé phenomenon. As my panel at Decanter World Wine Awards would attest, in the main Portugal’s entry-level rosés have failed miserably to build on the success of Mateus Rosé thanks to clumsy use of residual sugar and a lack of freshness.

Still, being fashionable, there’s a new rosé trend in town – the serious rosé and get this, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie make one – Chateaux Miraval from Provence! Even Mateus has gone upmarket with the launch of a new top tier range, Mateus Expressions (pictured). And I am delighted to say that I have recently found compelling evidence to suggest that Portugal may fare better with the new, quality and complexity-focused trend. Here are my serious Portuguese rosé picks of the bunch:

Principal Rosé Tête de Cuvée 2010 – Photo by Sarah Ahmed | All Rights Reserved

Principal Rosé Tête de Cuvée 2010 (Bairrada)

“Tête de Cuvée” is a wine produced from the first pressing of the grapes, which means it’s usually purer and of superior quality. Not least when, like this wine, it is made in the Rolls Royce of presses – a Coquard Champagne press – from the first (whole bunch) pressing (600l) of Pinot Noir destined for the sparkling wine (reviewed below). The pressed juice is then gravity run into small tanks (gently does it again) which also accounts for its super-pale pinky-beige hue and subtle, saline and savoury palate. Creamy but fresh and gently fruity (rhubarb/strawberry), it is very long and persistent. A serious gastronomic rosé –quite possibly the best I’ve tasted from Portugal. Excellent. 12.5% abv

Colinas Espumante Brut Rosé 2009 (Bairrada)

A very impressive salmon-coloured 100% Pinot Noir fizz which was aged for three years on the lees. It has great verve and tension. Just a hint of greenness rachets up the overall impression of tightness and dryness. A long, focused, dry finish has a very persistent fine bead. Lovely structure. Excellent. 12.5% abv

Casa de Saima Rosé 2013 (Bairrada)

Sticking with Portuguese grapes this time (Baga with just a dash of Touriga Nacional) this pale but bright Bairrada rosé is fabulously saline, fresh and dry. Baga’s firm acid backbone brings great energy and line to its delicate crunchy red fruit 9think cranberries). 13% abv.

Casa Ferreirinha Vinha Grande Rosado 2012 – Photo by Sarah Ahmed | All Rights Reserved

Casa Ferreirinha Vinha Grande Rosado 2012 (Douro)

Sogrape owns the Casa Ferreirinha and Mateus brands. While the top tier Mateus Expressions range is still very commercial (sweet) this seriously pale dry rosé firmly ticks both quality and complexity boxes. Sourced from 100% Touriga Nacional (which seems to work very well for rosés) and from the highest point of Quinta do Sairrão (at c. 650m), it’s delicately fruity, with a textured (gently creamy), spicy, savoury (nutty), mineral palate. A lovely unshowy yet sophisticated rosé, with finely balanced acidity. Very good. 12% abv

Quinta do Perdigão Rosé 2013 (Dão)

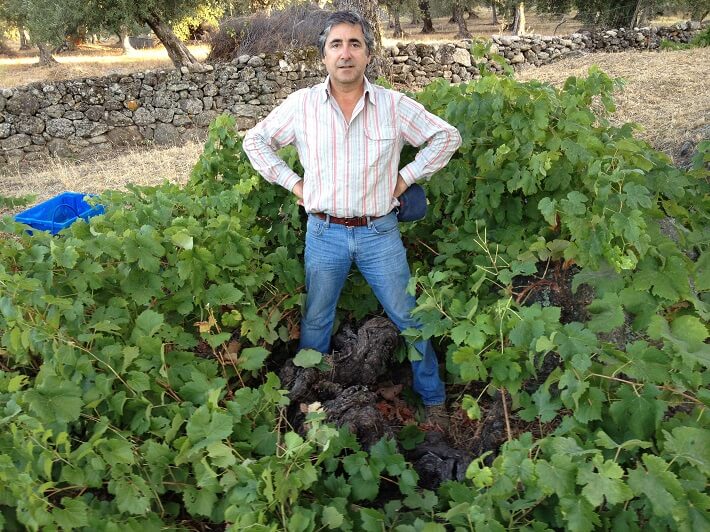

Full-time architect and full-time organic wine grower/maker José Perdigão is wont to give 300% to everything and, when he told me that this is the most serious rosé which he has made, I knew I was in for a rare treat. Compared with my other recommendations it’s a really deep pink hue – akin to the colour of stonking Australian Grenache rosés! It’s similarly muscular on the palate too. The reason? In 2013, the Dão experienced challenging conditions around harvest with spells of heavy rain and bursts of hot weather. Some of the fruit for this wine came in at very high baumé (with a potential alcohol level of 15.5 to 16%!) In consequence, Perdigão very cleverly introduced grape stems to the ferment for the first time, which brought perfume, freshness and helped lower the alcohol degrees. So at the end of the day, you get a win win – fabulously exuberant (red berry, currant and cherry) fruit and good body with balance. As for complexity, the Dão’s signature mineral and floral notes are well present in this Touriga Nacional, Jaen and Alfrocheiro blend. As Perdigão puts it, “it’s not a swimming pool rosé.” He recommends pairing it with dried tuna and wasabi. Highly original (perhaps even a one off given the vintage) – very good. 13.5% abv

José Perdigão – Photo by Sarah Ahmed | All Rights Reserved

Julia Kemper Elpenor Rosé 2013 (Dão)

Kemper’s rosé is also made from certified organic fruit but it couldn’t be more different. Made from 100% Touriga Nacional it’s pale and ultra delicate with gentle red fruit and floral (violets) notes. Deliciously crisp and dry with fresh, mineral acidity.

Muxagat MUX Rosé 2012 (Douro)

This is a really interesting rosé – I’m tempted to say intellectual, but I think that might be pushing it too far! Anyway, what I mean is that it bears little resemblance to the sweetish cheap and cheerful pink wines to be found in every corner shop and supermarket. All of which stands to reason given that MUX is sourced from a very high vineyard at 700m, moreover is influenced by the kind of dry, savoury rosés which Mateus Nicolau de Almeida’s southern French friends like to drink on a summer’s day (think Provence, Bandol, Tavel). A blend of Tinta Cão and Tinta Barroca which is fermented and aged partly in tank, partly in (old) barrel, this pinkish beige wine is creamy but dry and savoury with good acidity, lifted floral and dried spice notes and a hint of chocolate to its lingering finish. Much nicer than that sounds! Very good. 13% abv.